Mineralogia, petrografia, geologia

Mineralogia, petrografia, geologia

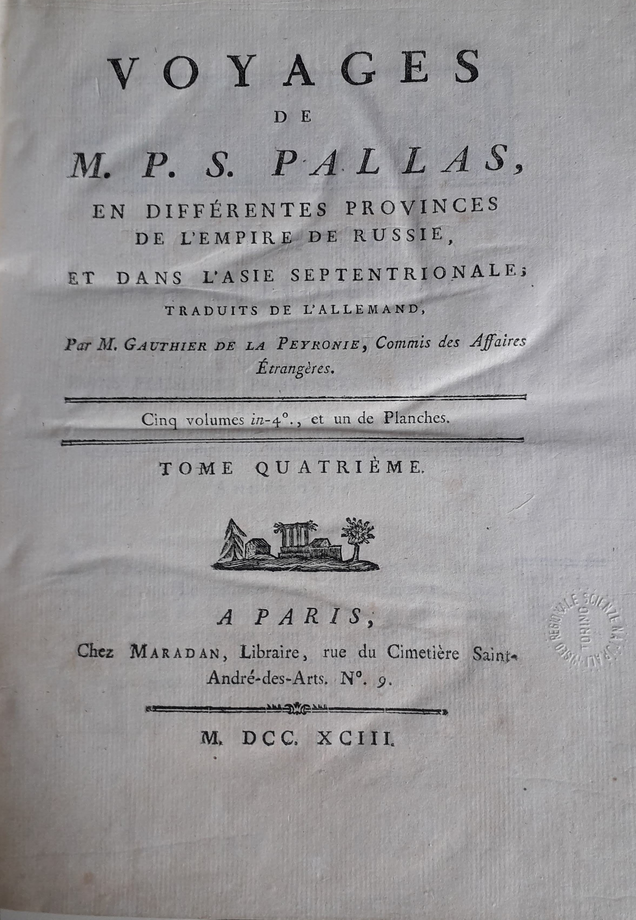

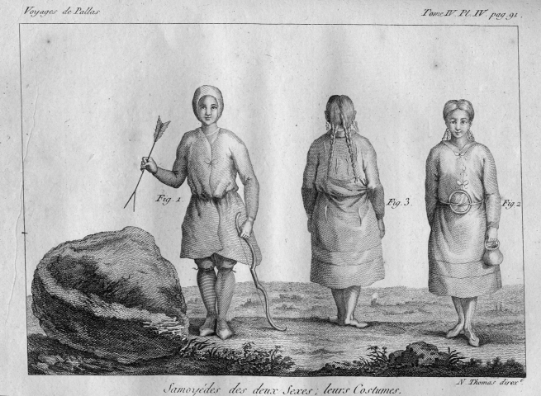

Nel 1772 vicino a Krasnoyarsk (Siberia), il geologo e zoologo tedesco Peter Pallas trova e descrive un’enorme massa di ferro (680 kg) di dubbia origine.

Già all’inizio del XVIII secolo alcune tribù della Siberia erano a conoscenza della presenza, in queste aree, di un enorme masso di ferro, che si diceva caduto dal cielo, e per questo ritenuto sacro.

Nel 1794, a seguito degli studi del fisico Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni, venne certificata l’origine extraterrestre del materiale rinvenuto, che prese il nome di “pallasite”, in onore del suo primo scopritore.

“Pioggetta” di sassi a Siena

Nello stesso anno, nella dissertazione Sopra una pioggetta di sassi accaduta nella sera de’ 16 giugno 1794, l’abate camaldolese Ambrogio Soldani descrisse una caduta di pietre in territorio senese, ipotizzandone l’origine extraterrestre.

Dove sono ora quei sassi?

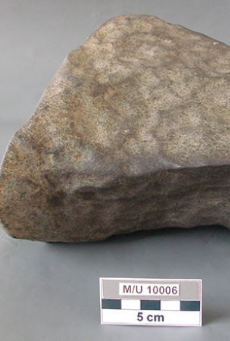

Le collezioni del MRSN conservano frammenti dei campioni delle meteoriti Siena e Krasnojarsk.

Ma cosa sono le meteoriti?

Meteorite (dal greco metéoros) = che sta in aria: corpi che riescono ad attraversare l’atmosfera senza consumarsi completamente e cadono sulla superficie terrestre.

La maggior parte delle meteoriti è rappresentata da frammenti di asteroidi, risultato della reciproca collisione di questi corpi celesti orbitanti attorno al Sole, soprattutto nella “fascia degli asteroidi”, fra Marte e Giove.

Hanno importanza scientifica?

Si tratta di reperti di importanza scientifica eccezionale, in quanto possono fornire indicazioni sulla composizione del sistema solare nelle prime fasi della sua formazione. Ad oggi ne sono state catalogate oltre 60.000, di cui circa la metà rinvenute in Antartide.

Da dove viene il loro nome proprio?

Le meteoriti sono contraddistinte da un nome che deriva, in genere, dalla località o dall’elemento geografico più vicino al punto di ritrovamento. La data associata a una meteorite può essere quella di caduta, se l’evento è stato osservato direttamente, oppure di ritrovamento se avvenuto in un tempo successivo.

Quanto sono grandi (o piccole)?

Il peso complessivo della massa originale può variare da pochi grammi fino a oltre 60 tonnellate (meteorite Hoba in Namibia).

Esiste una classificazione?

La classificazione “tradizionale” ordina le meteoriti in tre gruppi, in base alla composizione mineralogica e all’aspetto morfologico:

STONE, IRON E STONY-IRON

- aeroliti o meteoriti litoidi (da litos = pietra) o stone: costituite essenzialmente da minerali silicatici (ad esempio olivina, pirosseni e plagioclasi). Rappresentano poco più del 95% delle meteoriti note;

- sideriti (da sideros = ferro) o meteoriti metalliche o iron: sono formate quasi esclusivamente da leghe ferro-nichel, in cui i due elementi sono presenti in proporzioni variabili. Sono circa il 4% delle meteoriti conosciute;

- sideroliti (letteralmente pietre di ferro) o meteoriti miste o stony-iron: sono costituite da una parte metallica e da una silicatica in misura variabile, più o meno intimamente mescolate. Costituiscono solo lo 0,5% circa delle meteoriti note.

132

collezioni geologico-litologiche provenienti dal Museo di Geologia e Paleontologia dell'Università di Torino: si tratta di 13.138 campioni, per complessivi 26.884 esemplari

16.400

esemplari costituiscono la collezione mineralogica, costantemente incrementata da donazioni e raccolte effettuate dal personale del museo

800

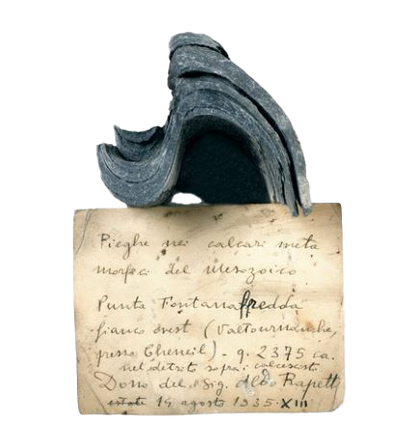

sezioni sottili di rocce da tutto il mondo collezionate dal prof. G. Spezia, direttore del Museo di Mineralogia e Petrografia dell'Università di Torino tra il 1878 e il 1911

6.000

campioni della collezione giacimentologica

500

campioni della raccolta storica di rocce e fossili della Sardegna, realizzata dal generale A. Ferrero della Marmora

Da cosa sono costituite le collezioni della sezione?

Da campioni di minerali e rocce, campionature di trafori, plastici e modelli tridimensionali, strumenti, attrezzature minerarie e di laboratorio.

La loro storia è interessante?

La storia delle meteoriti presenti al MRSN segue di pari passo quella delle raccolte mineralogiche e geologiche, che si sono progressivamente formate a partire dal 1739, anno di istituzione del Museo dell'Università di Torino, attraverso acquisti, lasciti, donazioni, scambi e raccolte gestite da scienziati e ricercatori.

Tra questi spiccano i nomi di Étienne Borson, primo Direttore del Museo di Mineralogia dell'Università di Torino e di Angelo Sismonda, suo successore, che ampliò le collezioni e riorganizzò la catalogazione secondo un sistema tuttora in uso. Sismonda realizzò anche importanti acquisizioni e curò numerosi scambi con i grandi Musei mineralogici dell'epoca.

Nel 1878 la Direzione passò al mineralogista Giorgio Spezia, che ampliò l'opera del suo predecessore. Alla fine del XIX secolo, il Regio Museo Mineralogico di Torino, ricco di oltre 15000 campioni, era considerato fra i più importanti d'Europa.

Dopo una lunga fase di quiescenza, nel 1980 la collezione fu ceduta al Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino, che ha successivamente acquisito più di 15000 nuovi campioni di minerali. La collezione ammonta attualmente a oltre 65000 esemplari tra minerali, rocce e meteoriti.

APPROFONDIMENTO

Angelo Sismonda

Angelo Sismonda (Corneliano d’Alba, 1807 – Torino, 1878) si appassionò alla mineralogia seguendo prima le lezioni di Étienne Borson, titolare della cattedra di mineralogia presso l’Università di Torino, poi quelle di Élie de Beaumont e di altri mineralogisti alla Sorbona, all’École des mines e al Muséum d’histoire naturelle a Parigi. Nel 1828 fu richiamato a Torino da Borson, che gli offrì l’incarico di assistente e poi quello di professore sostituto. Alla morte di Borson, divenne titolare della cattedra e nel 1833 ottenne la direzione del Museo di Geologia e Mineralogia. Nel 1834, durante un’escursione scientifica sulle Alpi marittime e sugli Appennini liguri, assieme a Élie de Beaumont e Ours-Pierre-Armand Dufrénoy, rispettivamente ispiratore e direttore della prima carta geologica della Francia, maturò l’idea di realizzare un’analoga carta geologica del Piemonte e della Savoia.

Nel 1846 venne incaricato dal Re Carlo Alberto di provvedere alla stesura di una Carta Geologica di massima degli Stati Sardi in Terraferma. La prima edizione di questa, revisione e sintesi dei rilevamenti parziali pubblicati in precedenza, fu realizzata tra il 1862 e il 1866, per cura del Governo di S.M. Vittorio Emanuele II Re d’Italia. Colorata ad acquerello su base topografica del 1857 e montata su tela, la Carta costituisce il primo esempio di cartografia geologica ufficiale del neonato Stato Italiano. È inclusa anche una legenda composta da 20 caselle e un elenco dei minerali utili, nonché le principali masse di lignite, antracite e gesso, oltre alle sorgenti di acque minerali. In particolare per la prima volta vengono attribuiti al Giurassico i terreni metamorfici della Zona Piemontese (gli attuali calcescisti) ritenuti fino ad allora molto più vecchi (archeozoici).

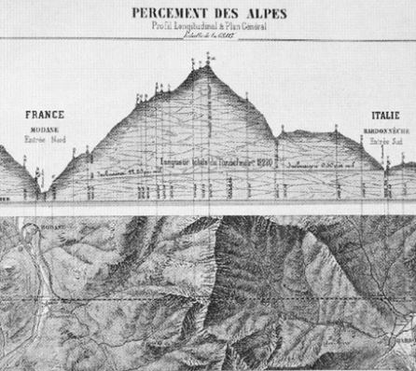

Sismonda contribuì anche al progetto della galleria del Fréjus, opera considerata irrealizzabile a causa della lunghezza (circa 12 km), ma che risultò possibile grazie all’impiego di un nuovo perforatore pneumatico messo a punto da Germano Sommeiller.

L’opera fu conclusa nel 1870, dodici anni prima del previsto.

Fu membro dell’Accademia delle Scienze di Torino, dell’Accademia Leopoldina, della Società italiana delle Scienze, della Pontificia Accademia dei nuovi Lincei e della Società reale di Napoli.

Nel 1953 divenne preside della Facoltà di Scienze e direttore della Scuola di Farmacia.

Negli ultimi anni subì una duplice amarezza: la messa in discussione delle teorie litogenetiche di Élie de Beaumont, sulle quali aveva fondato le sue ricostruzioni geologiche alpine (smontate da Quintino Sella e Felice Giordano) e il trasferimento del Museo di Geologia e Mineralogia a Palazzo Carignano, dove il criterio espositivo a gradini, di cui era un convinto sostenitore, fu abbandonato.

INFORMAZIONI

Quante cose si possono imparare sul mondo naturale? Scoprilo al Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali!